For years now, we have been searching for a way to make our birdbath packaging more sustainable. Our starting idea is that the packaging should be able to be composted in the very gardens our birdbaths occupy. It doesn’t make sense to offer a product that beautifies one part of our landscape but sullies another with discarded packaging.

It turns out that this is an unexpectedly difficult challenge. The packaging industry has very limited options for offering accessible, flexible, compostable packaging that can adequately protect objects in transit. Innovative technologies do exist, but they generally serve specific uses such as food packaging. In this blog post we detail some of our own home-grown Research and Development, exploring how mycelial structures (mushroom roots) can be grown over recycled organic substrates. So far, we have discovered that mycelial structures are an amazing natural resource that will functionally satisfy our needs but, for various reasons, fail to meet the business case.

–

Currently, we use plastic pool noodles wrapped around the edges of our dishes. They work wonderfully in cushioning the birdbaths and protecting them from damage during shipping, but they go straight to landfill after one use. Pool noodles are made from a type of expanded polyethylene foam, which is not easily recycled and takes thousands of years to break down in the environment.

Our main difficulty has been finding a sustainable material that is robust enough to cushion the bird baths from damage without collapsing. Starch-based packing peanuts and paper-based materials just haven’t been strong enough to protect the edge of the birdbaths from their own weight when dropped on their edge.

Hannah, one of the Mallee Design team, is a mycophile: a person who loves fungi. Hannah suggested growing our own sustainable packaging using mushroom roots. Mushroom ‘roots’, scientifically called mycelium, can be grown on waste materials such as wood, straw, coffee grounds and husks to create compostable materials. The cell walls of mycelium are made out of chitin, the same fibrous substance that builds the exoskeletons of crustaceans such lobsters and crabs. This is what makes it a structural sound material that can have similar properties to plastics. Several companies have already been using the technology to make biodegradable packaging and leather-like textiles in America and Europe (eg. see Ecovative Design).

We began some small scale experiments to see if we could successfully grow the fungi ourselves. We chose a species called Ganoderma (a type of reishi mushroom used in traditional Chinese medicine) because it produces 3 types of mycelium. This makes it better able to hold a substrate together and in science jargon is called ‘trimitic’. Some of the mycelium is very thin and highly branched, some is thick and skeletal, and some is great at binding different parts of the mycelium together, making it very structurally robust overall. There are other trimitic species available, such as Turkey Tails (Trametes versicolor), but we chose a Ganoderma because it is known to be used successfully in mushroom biotechnologies already.

Our first test used waste hardwood sawdust, from a local woodwork workshop, as the growing substrate. A second substrate we tested was sugarcane mulch, a less dense material that has the benefit of longer strands which, we thought, might help hold the finished product together. To each base substrate (sawdust/sugarcane) we added wheatbran, which acts as a high-protein, easily digestible supplement for the mycelium to use as food. Because sawdust and sugarcane is relatively nutrient poor and difficult for the mycelium to digest, adding wheatbran gives growth a head start. A third element we added was water, crucial for the metabolism of almost all life, including fungi!

After creating our supplemented substrate mix, our next step was to kill off any contaminants (such as bacteria or other fungi) already present in the substrate, which would interfere with the Ganoderma’s growth. We did this by placing the substrate in grow bags and heating them to temperatures above 100°C in a standard kitchen pressure cooker for several hours. Grow bags are made from industry standard polypropylene plastic, which can withstand the high temperatures of the pressure cooker, and which also have filter patches that prevent pathogens entering the bag once they’ve been taken out of the pressure cooker. The filter patches stop pathogens getting in, but still allow the exchange of gases such as oxygen and CO2, which are important for the mycelium’s growth.

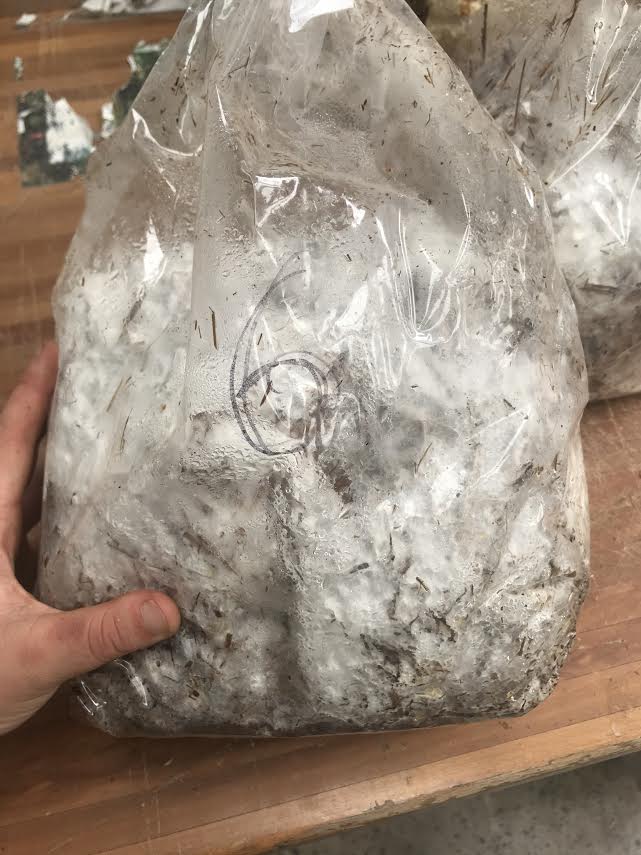

Once the substrate had cooled we inoculated it by manually mixing grain spawn through the material with our sanitised, gloved hands. Grain spawn is sterilised grain coated in the spores of a mushroom species and we purchased ours from an Australian supplier. When the spores on the grain encounter an appropriate substate they start to grow into baby pieces of mycelium which look like fuzzy, white threads. These threads work their way through the substrate by digesting the sugars in the wood until they eventually colonise the material and prepare for fruiting (producing mushroom bodies).

Our mycelium formed a spongy white shell around the outside of our blocks. Once enough of a structure had formed, we removed the blocks from the grow bags and baked them in the oven until completely dried out. The oven drying process and heat desiccates the mycelium, basically killing it, and prevents it from fruiting (producing mushrooms). Drying it this way also makes sure the material is sterile and won’t carry spores or go mouldy when we use it as packaging.

The images below show our blocks grown on sawdust and sugarcane respectively.

The dried sawdust blocks were relatively heavy (~500g) with a smooth, leathery texture on the outer surface. They were denser than the pool noodles we’d been using but still had the bit of give needed to cushion the birdbaths and absorb shock. In the photo below you can see how the material still held its shape when squeezed. The sugarcane mulch blocks were lighter with a more crackly texture. They tended to break apart a little or collapse when firmly squeezed but maintained their overall shape on impact. Both substrates had the potential to work well as packaging replacement to the pool noodles.

What we produced was the beginnings of a viable packaging solution! A material that mimicked the characteristics of plastics that we wanted, but which would degrade easily in the environment and could be added to people’s home composts. We placed some of the finished material in our own composts and as a light mulch on pots plants. It was well on its way to breaking down within a couple of months

The business case

Once the physical properties of the finished material were deemed satisfactory, we then started planning a production schedule. This is where our research hit real problems. The effort, time and physical space required to manufacture these compostables for our small-scale enterprise is excessive.

Firstly, we’d need to figure out a way to make moulds in the shape of the packaging we wanted and/or invest in someone to make them for us. A run of enough packaging for 20 birdbaths would require 80 moulds. Creating the moulds is do-able but requires careful consideration and testing of the design and an initial start-up cost. We may also need to adapt the growing process to ensure the sterilised substrate can be transferred into the moulds with very low risk of contamination.

A second difficulty would be sourcing a reliable and local supplier of waste substrate appropriate for growing the mycelium. For those 80 moulds we would need approximately 40kg of sawdust or 16kg of sugarcane per run. Also do-able, but potentially time-consuming if it required picking up from the supplier.

Sterilising 16-40kg of substrate per run is one of the biggest challenges and extremely difficult without a commercial size autoclave. With our home pressure cooker we can only sterilise about 1.5kg of substrate at a time, every two hours. That would equal over 50 hours of sterilising per run using our current equipment, and isn’t at all feasible. Drying the mycelium blocks in the oven at the end of the growing process would also need to be scaled-up somehow.

Another big drawback is the time required to grow each packaging block. It takes one full month from the day sterilisation starts to oven-drying process at the end to get the finished packaging product. This time-lag means there needs to be a large amount buffer stock in storage to meet fluctuating demand for products throughout the year. The physical space required to hold 80 moulds for one month is approximately 2m3.

The final consideration is the labour and time investment required even if we streamlined the above processes at much as we possibly could. We estimate that it would take one employee at least 16 hours or two days/week to make this happen for us. Our conclusion is that producing this packaging it is an entirely new business, waiting to happen, in its own right.

So, where to now? Now, we are collaborating with designers in Sydney to create a packaging material out of cardboard pulp – a material similar to that which is used in egg cartons. This cardboard packaging is recyclable and can be mass produced in China but is not without its own challenges. It has proven difficult to design a packaging piece sturdy enough to protect our birdbaths during travel but we are close to finalising the design now. Manufacturing in China has the downside of producing a lot of packing miles (more use of fossil fuels to get the packaging to us) but it is the most viable and cost-effective solution we have found.

Below is a photo of all the packaging options we’ve tried so far, from pool noodles to mycelium blocks to cardboard moulds. None of them are perfect but we are doing our best to make our business as sustainable as we can.

Despite not choosing the mycelium blocks as our final packaging solution, we were inspired by the ability to create such a practical, organic material. One that also has the potential to be used aesthetically in other design projects. Our next endeavour is to try to create an outdoor chair made from mycelium using a similar method.

Stay tuned,

Hannah and Etienne

Leave a Reply